Our Mission: Empower Do-It-Yourself Investors with Free Academic-based Research & Resources for Life-long Investing

Don’t get fooled again: 3 ways investors are tricked, and 6 ways to protect yourself

Reprinted courtesy of MarketWatch.com

Published: November 15, 2023

To read the original article click here

I want to make three main points.

First, the “facts” of investment history aren’t always what they seem. This can fool us into making flawed decisions.

Second, emotional impatience and wishful thinking can fool us into believing we know more than we do.

Third, Wall Street actively fools us in various ways, and most of the financial media passively goes along.

We think we know certain things to be true.

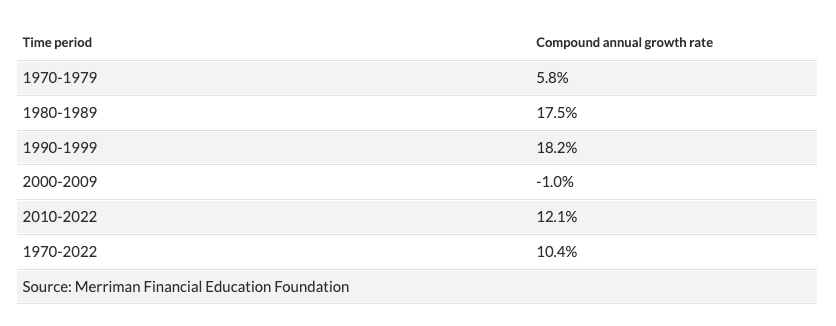

For example, over the long term, the S&P 500 SPX has compounded about 10% a year. That’s pretty easy to verify; the index is fixed in its makeup, and there’s nothing nefarious going on behind the scenes.

However, “long term” can mean different things.

It’s true that the very-long-term compound return of the S&P 500 has been around 10%. But most of us don’t invest for 90-plus years.

At the end of 1999, the S&P 500 had grown at more than 17% for a quarter of a century. In just the most recent five years (1995 through 1999), it had compounded at 28.6%.

As the new century shoved the old one aside, fortunes were being made as technology was transforming the world from analog to digital.

Surveys of investors indicated many expected the next 10 years would produce annual compound gains of 20% to 30%. As a result, far too many people fooled themselves into complacency.

And then financial reality — in the form of a couple of severe bear markets — ruined the party. (See the 2000-2009 result in the following table.)

Since 2000, the index has compounded at about 6.5%, leaving a generation of investors wondering if they can trust the past.

Now, 90 years of history may be too long to seem relevant. But a single year is certainly much too short to be meaningful.

Should investors look at returns 10 years at a time? The following table tells a story.

The first three decades shown in the table produced a positive picture. But the major shocks in the first decade of the new century led millions of investors to bail out — and to miss the positive period of 2010 through 2022.

Here’s another way that facts are deceptive: I said earlier that the S&P 500 has compounded about 6.5% since 2000. That’s true, but only for investors who stayed the course.

Because so many people fled the market, the actual compound return of real-life investors in those years was probably far less than 6.5%.

I’m a big fan of using U.S. small-cap-value stocks to diversify against the S&P 500. From 2000 through 2022, a 50-50 combination of those two asset classes achieved a compound annual growth rate of 13.7%, compared with 10.4% for the S&P 500. And yet the S&P 500 outperformed small-cap value from 1990 through 1999, and again from 2010 through 2022.

However, if you think I’ve just told you “the facts” on this matter, you might be wrong.

In general terms, investors agree on what we mean by small-cap value stocks. But several widely used indexes track that asset class using different definitions, different management methods, and different weightings.

The resulting growth rates for “small-cap-value stocks” often differ by 2 percentage points or more, depending on what index you check.

We learn in school that history is “true.” But, as any competent historian could tell you, history is the result of a series of interpretations, based on selected data and (inevitably) incomplete information.

Fooled by ourselves

As investors (and humans, for that matter), we are capable of enormous feats of self-deception.

We look for (and usually find) information and arguments that support what we believe — or what we hope.

We want to believe what we understand.

We want to believe we know what’s important and what’s not.

We prefer what’s familiar, and we put much more stock in recent returns than those from past times, especially before we were paying attention.

We are easily deceived by normal market losses, seeing them as evidence that “things have really changed” for the worse.

Because investing seems to have so many moving parts, we find it comforting to rely on friendly experts who are available to help us.

That leads to my third main point.

Fooled by Wall Street

Entire books (including one that I wrote some years back) have been written on this point. A few highlights:

Brokers and salespeople of all stripes nearly always want us to do something other than what we’re already doing. That’s what keeps them in business.

Because investors give the most credibility to recent returns, salespeople inevitably promote products that have been performing well lately — and never bother to tell us that they started recommending those products only after that superior performance had occurred.

The financial media mostly accepts Wall Street’s interpretations of history, even though the result can be misleading.

Example 1: Morningstar and other sites report the average performance of mutual funds, but they include only funds that had good enough performance to survive without being closed or (more likely) merged into other funds.

Example 2: The same resources conveniently ignore the fact that upfront sales charges required to buy load funds forever reduce investors’ returns. They report those funds’ returns as if the sales commissions were never paid.

The upshot

When we are fooled by history, fooled by ourselves, and fooled by Wall Street, one unfortunate result is that we are left with unreasonable expectations of the returns we are likely to actually achieve.

Couple this with a widespread tendency to procrastinate about investing for retirement, and you have a recipe for disappointment, disillusionment — and sometimes worse.

What to do

If we can’t fully trust the past and we can’t fully trust ourselves and we can’t fully trust Wall Street, is there still hope?

Fortunately, yes. Here are six recommendations.

First: If you’re not retired and not regularly saving money, start now. Even if you must start small, do it. Start this week.

Second: Diversify. Own hundreds if not thousands of stocks through mutual funds or ETFs. And own multiple asset classes.

Third: If you’re young, don’t be afraid of bear markets. In the long run, they let you buy valuable assets at bargain prices. You can easily do this using dollar-cost averaging.

Fourth: Control your level of risk by owning bond funds as well as equity funds.

Fifth: When you plan for your needs, assume that future returns may be lower than past returns. This might mean you’ll need to work a few years longer before you retire — or learn to live on less after you retire.

All those recommendations are addressed in a series of articles I wrote earlier this year.

Sixth: While you’re busy doing all that, remember that the future will always be uncertain. Live your life as if every day really matters. It does.

If you’d like to learn some good, bad and ugly details of small-cap-value stocks, don’t miss this video.

Richard Buck contributed to this article.

Paul Merriman and Richard Buck are the authors of We’re Talking Millions! 12 Simple Ways to Supercharge Your Retirement.

Delivery Method. Paul Merriman will send stories to MarketWatch editors on a biweekly basis. Licensor may republish such stories 24 hours after publication on MarketWatch with the attribution.