Our Mission: Empower Do-It-Yourself Investors with Free Academic-based Research & Resources for Life-long Investing

This is the worst investment advice I know — and you may be taking it

Reprinted courtesy of MarketWatch.com

Published: July 27, 2023

To read the original article click here

Lately I have been wondering how to do a better job of helping investors protect themselves from toxic sales pitches that pretend to be helpful advice — pitches that are really about generating income for the salesperson.

What I’m about to say is harsh, but I believe it: Wall Street has become addicted to all the money it can make from confused and uneducated investors.

Far too many investors don’t realize they are willingly helping Wall Street — and some people in the financial media — rob them of billions of dollars every year.

That’s right, billions.

The outrage on my mind lately is load funds, mutual funds that require investors to pay a sales commission for the “privilege” of owning portfolios with too-high taxes, too-high operating expenses, and dubious active management.

After slick sales presentations that fail to mention these drawbacks, people commit themselves to investments that will almost certainly underperform the very stock market they are trying to beat.

If you’re reading this article, I suspect you know better than to squander your own money this way. But if you understand what’s going on, perhaps you can help a friend or relative avoid this trap.

So let me take you through a scenario that works brilliantly for Wall Street. But more than 90% of the time, it works poorly for investors.

The sales pitch

Let’s say you have $10,000 to invest, and you aren’t sure where the money should go. You know you need professional guidance, and in one way or another you become acquainted with a broker.

They are friendly – perhaps even charming. They have a smiling face and an optimistic outlook, assuring you they can connect you with managers who have very successful track records. They ask you to trust them to do what’s best for you. After all, they can’t stay in business without happy customers. As they’ll ask you about your long-term goals and your investing experience, they’ll casually include some questions designed to find out what’s most important to them: how much money you have available to invest, and how easy it will be to talk you into buying what they want to sell.

The subpar product

This chatty, casual conversation will soon come around to discussing a very large mutual fund that people have trusted to manage more than $110 billion.

I’m using the American Funds Investment Company of America AIVSX, -0.29% for my example. It’s been highly regarded for many years, and its sales structure is typical of load funds.

As you sit with your new “friend,” you are pleased to learn the fund invests in well-known companies like Microsoft MSFT, 2.43%, General Electric GE, -0.41%, Amazon AMZN, 3.07%, Apple AAPL, 1.68%, and Abbott Laboratories ABT, 0.20%. The broker tells you they have lots of clients who happily own it. They might even say their parents own this fund. You breathe a sigh of relief, believing you have finally found somebody who’s on your side. You reach for your checkbook.

On the other side of the desk, the broker may hide their delight at how easy this was.

What you won’t be told

Unless you study the printed disclosures the broker is required to give you, you’ll probably be unaware that you’ll have a guaranteed loss as soon as you write your check.

You think your $10,000 is being invested in the fund. But because of a 5.75% sales commission, known as a load, only $9,425 of your money is invested. The other $575 is your money today and Wall Street’s money tomorrow.

As we shall see, if you keep your money in the fund, the opportunity cost of that $575 will grow and grow.

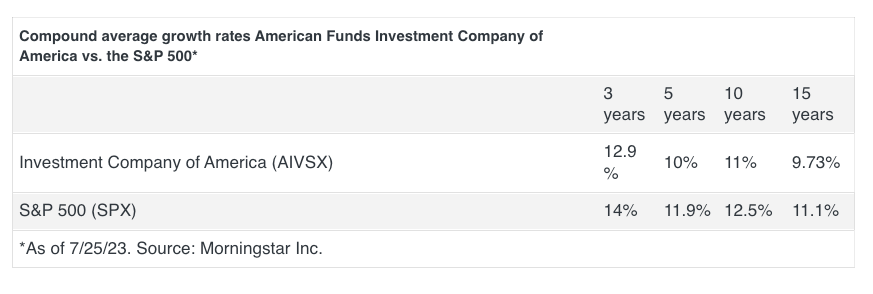

Your broker is unlikely to tell you the fund you’re buying has underperformed (by significant margins) its large-cap blend peers, as well as the S&P 500 index, in the most recent three-year, five-year, 10-year and 15-year periods.

Here are those numbers:

You won’t be told that in addition to below-average performance, you have just:

- Signed up for active management, which historically has about a one-in-ten chance of even being equal to, much less beating, its large-cap blend benchmark index.

- Signed on for higher portfolio turnover, which is likely to increase your taxes.

- Agreed to have nearly 5% of your investments held in cash instead of being invested.

- Agreed to pay roughly 20 times as much in regular operating expenses as you would in a comparable index fund.

Worse still, your underperformance is, in reality, a lot worse than it appears in the table.

By choosing this load fund, you’ve given up the opportunity to have $575 working for you instead of for Wall Street. You have to do a little math to figure this out, but if you had invested $10,000 in the S&P 500 for the past 15 years, your investment would have become worth nearly $59,000.

Instead, you invested only $9,425 in a fund that earned only 9.73%. The upshot: By paying the upfront load and leaving your money in for 15 years, you effectively left $13,068 on the table.

Need I go on? Yes.

There’s one more counterproductive thing you’ve just done: You have established yourself as a willing target for further sales pitches, some of which could be much worse for you. You’re now on their list.

I have talked to a lot of retired brokers who once sold load funds. I have asked them if they follow the advice they gave to their customers: to buy load funds. Almost always they tell me no, their own money is invested in index funds.

The easy alternative

An adviser who truly had your interests in mind could have helped you invest your entire $10,000 in an S&P 500 index fund.

Maybe best of all, that would keep you off most lists of potential suckers. Because let’s face it, there’s very little money to be made selling index funds. A few years back I highlighted that topic.

A few facts

It’s easy for me to get wound up on this topic.

Investors choose (or are sold) active management in order to beat the market. The odds of success are slim, and they diminish over time.

According to the widely respected SPIVA Scorecard for 2022, only 21% of all U.S. domestic mutual funds matched or outperformed their benchmarks for the past three calendar years. Over five years, the percentage dropped to 12%; after 15 years, to 6%.

If you want to beat the market through active management, you’re very likely to fail. On the other hand, if you want above-average returns, you’re virtually guaranteed to get them with an index fund.

Two quick pieces of advice

First, if you need professional advice, hire a fiduciary adviser who charges by the hour. Whatever you pay, you can be sure their recommendations will be chosen to promote your interests, not theirs.

Second, no matter what recommendation you get, here are a few red flags that should prompt you to slow down and consider whether this is something you really want to do.

Red flag 1. Any adviser who recommends investment products issued by an insurance company.

Red flag 2. Any adviser who recommends actively managed funds; that includes virtually all load funds.

Red flag 3. Any adviser who receives income from sources other than clients.

Red flag 4. Any fund with annual operating expenses higher than 0.25%.

Red flag 5. Any fund with portfolio turnover above 10%.

There’s much more to say on this topic, and I’ve recorded a podcast “The worst investment advice I know,” to go with this article.

Richard Buck contributed to this article.

Paul Merriman and Richard Buck are the authors of “We’re Talking Millions! 12 Simple Ways to Supercharge Your Retirement.” Merriman is also the author of “Get Smart or Get Screwed.”

Delivery Method. Paul Merriman will send stories to MarketWatch editors on a biweekly basis. Licensor may republish such stories 24 hours after publication on MarketWatch with the attribution.

The Merriman Financial Education Foundation is a registered 501(c)(3) organization founded in 2012.

All donations are used to support our work. Deductions are permissible to the extent of the law.

Contact us at info@paulmerriman.com

All information on this site is provided free of charge (with the exception of books for sale) and is funded in full by The Merriman Financial Education Foundation.

Anyone wishing to use this educational information in web-based or printed materials are welcome to do so with the following attribution and link:

“This information freely provided courtesy of PaulMerriman.com.” We would also appreciate a copy and link of where it has been published via email.

All Rights Reserved